doi.org/10.20986/revesppod.2025.1741/2025

REVISIÓN

Thermography for diagnosis and monitoring of peripheral artery disease: a narrative review

La termografía como método de diagnóstico y monitorización de la enfermedad arterial periférica: una revisión narrativa

Beti Iuliana Motoi1

Carmen Soriano-Marqués1

David Montoro-Cremades2

Jonatan García-Campos2

Javier Marco-Lledó2

1Práctica privada. España

2Departamento de Ciencias del Comportamiento y Salud. Universidad Miguel Hernández de Elche. Alicante, España

Abstract

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) is a prevalent medical disorder characterized by decreased blood flow in the arteries supplying the body’s peripheral tissues, primarily the lower extremities, due to partial or total arterial obstruction. Atherosclerosis is its leading cause, with prevalence increasing due to lifestyle changes, diet, and conditions such as diabetes mellitus. This bibliographic review aimed to determine the efficacy profile of thermography as a tool for diagnosing and monitoring PAD. We conducted a comprehensive search across Medline and Scopus, selecting articles published within the past 12 years including case reports evaluating thermography’s efficacy in PAD diagnosis. Findings indicate that thermography correlates with ankle-brachial index values and is useful for monitoring PAD in diabetes mellitus patients, thereby avoiding additional risks. Of note, professionals should not rely solely on clinical evaluation of foot temperature in diabetes mellitus patients. Infrared thermography proved effective in detecting temperature variations between the feet, suggesting its utility in PAD diagnosis. However, given that many factors influence normal skin temperature, thermography should not be the sole method for assessing PAD but rather a complementary tool in diagnosis and follow-up.

Keywords: Peripheral arterial disease, thermography, ankle–brachial index, diagnostic techniques and procedures, hemodynamic monitoring

Resumen

La enfermedad arterial periférica (EAP) es un trastorno médico prevalente, caracterizado por la disminución del flujo sanguíneo en las arterias que irrigan los tejidos periféricos, principalmente las extremidades inferiores, debido a obstrucciones arteriales parciales o totales. La aterosclerosis es su causa principal, y su incidencia se ve incrementada por factores como los cambios en el estilo de vida, la alimentación y la presencia de patologías como la diabetes mellitus. El objetivo de esta revisión bibliográfica fue determinar la eficacia de la termografía como herramienta para el diagnóstico y la monitorización de la EAP. Para ello, se realizó una búsqueda exhaustiva en las bases de datos Medline y Scopus, seleccionando artículos publicados en los últimos 12 años que incluyeran casos clínicos evaluando la eficacia de la termografía en el diagnóstico de la EAP. Los resultados indican que la termografía se correlaciona con los valores del índice tobillo-brazo y demuestra ser útil en la monitorización de la EAP en personas con diabetes mellitus, evitando riesgos adicionales. Se subraya que los profesionales no deben confiar únicamente en la evaluación clínica de la temperatura de los pies en pacientes diabéticos. En conclusión, la termografía infrarroja ha demostrado ser efectiva para detectar variaciones de temperatura entre los pies, lo cual sugiere su utilidad en el diagnóstico de la EAP. No obstante, dado que la temperatura cutánea normal depende de múltiples factores, la termografía no debe ser el único método para evaluar esta condición, sino un complemento en el diagnóstico y seguimiento.

Palabras clave: Enfermedad arterial periférica, termografía, índice tobillo-brazo, técnicas y procedimientos diagnósticos, monitorización hemodinámica

Corresponding author

David Montoro Cremades

dmontoro@umh.es

Received: 17-06-2025

Accepted: 10-09-2025

Introduction

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) is a condition characterized by partial or complete obstruction of blood flow in the arteries of the extremities, mainly the aortoiliac, femoropopliteal, and infrapopliteal arteries. It can be caused by atherosclerosis, resulting in restricted blood flow. In many cases, it is asymptomatic before causing pain in the lower limbs during movement (intermittent claudication), rest pain, or promoting the development of ulcers, infections, and, in severe cases, necrosis(1,2,3,4,5,6).

Currently, PAD represents an emerging public health burden as a result of population aging and increased rates of smoking, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus (DM). Its prevalence is estimated to be 3-10 % in the general population and 15–20% in individuals older than 70 years, increasing to 29 % in people with DM older than 50 years. Moreover, DM can also complicate the diagnosis and treatment of PAD, as neuropathy may alter pain perception(7).

PAD diagnosis is achieved using different techniques such as the ankle–brachial index (ABI), Doppler ultrasound, or toe pressure measurement (TPM) (2,3,4,5,6,7,8). Arteriography is considered the gold standard, but its routine use is limited because it is an invasive technique with inherent risks due to catheterization and exposure to radiation and contrast(1,2,6,7,9). Other diagnostic techniques also present limitations. For example, the reliability of ABI or Doppler is reduced if the patient has artery calcifications, and TPM cannot be measured in patients with amputation(2,3,4,5,7,9,10).

Thermography is a non-invasive technique that uses infrared cameras to measure the distribution of radiant thermal energy (heat) emitted from the surface of an object or body. This energy is converted into a map of radiation intensity differences, known as a thermogram, which represents a surface temperature map. Since it does not emit ionizing radiation, it allows for safe and unrestricted applications, enabling visualization of the thermal behavior of system(2,5,8,10,11,12).

It has been demonstrated that mean foot temperatures are lower in the PAD group than in healthy controls. Skin temperature differences > 2.2 °C between feet are more common in PAD patients than in healthy individuals; thus, significant thermal asymmetry may indicate a pathological process. However, despite its advantages, the available evidence on the use of thermography in PAD remains heterogeneous and scattered, making it difficult to draw firm conclusions about its clinical applicability(5,9,10). In this context, it is pertinent to synthesize and analyze the existing literature.

The aim of this narrative review is to determine whether thermography is an effective method for the diagnosis and monitoring of PAD.

Materials and methods

We conducted a narrative review of the literature. Searches were conducted across Medline and Scopus databases between March and April 2023 using the keywords “thermography,” “peripheral arterial disease,” and “ankle–brachial index,” limited to title, abstract, and keywords. Medline search strategy: “thermography” [Title/Abstract/OT] AND “peripheral arterial disease” [Title/Abstract/OT] AND “ankle–brachial index” [Title/Abstract/OT]. Scopus search strategy: TITLE-ABS-KEY (“thermography” AND “ankle–brachial index” AND “peripheral arterial disease”).

The inclusion criteria are: studies conducted in patients with lower-limb PAD diagnosed using thermographic techniques, clinical trials and reviews, human studies, articles in English or Spanish. The exclusion criteria are: studies investigating revascularization in PAD patients, articles employing smartphone-based thermal cameras as detection systems for PAD.

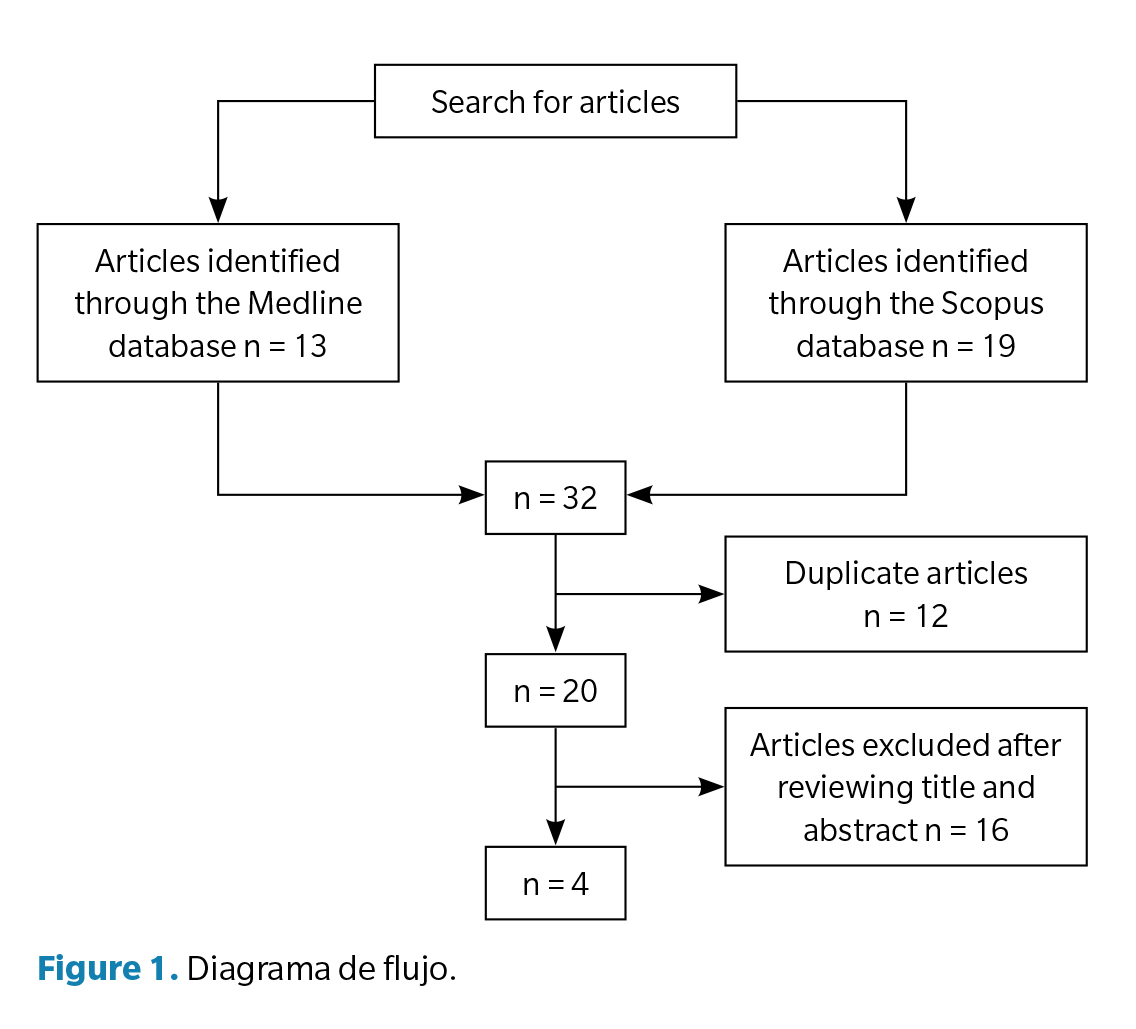

The Medline and Scopus searches yielded 13 and 19 results, respectively. After removing 12 duplicates, 20 unique articles remained. Two authors independently reviewed all studies, and discrepancies were resolved by a third author. During title and abstract screening, most studies were excluded for not meeting inclusion criteria—specifically those that did not use thermography as a primary evaluation tool, were experimental animal or simulation studies, were reviews, editorials, or conference abstracts without original data, or did not include a PAD population. Sixteen studies were excluded, leaving 4 articles for inclusion (Figure 1).

Results

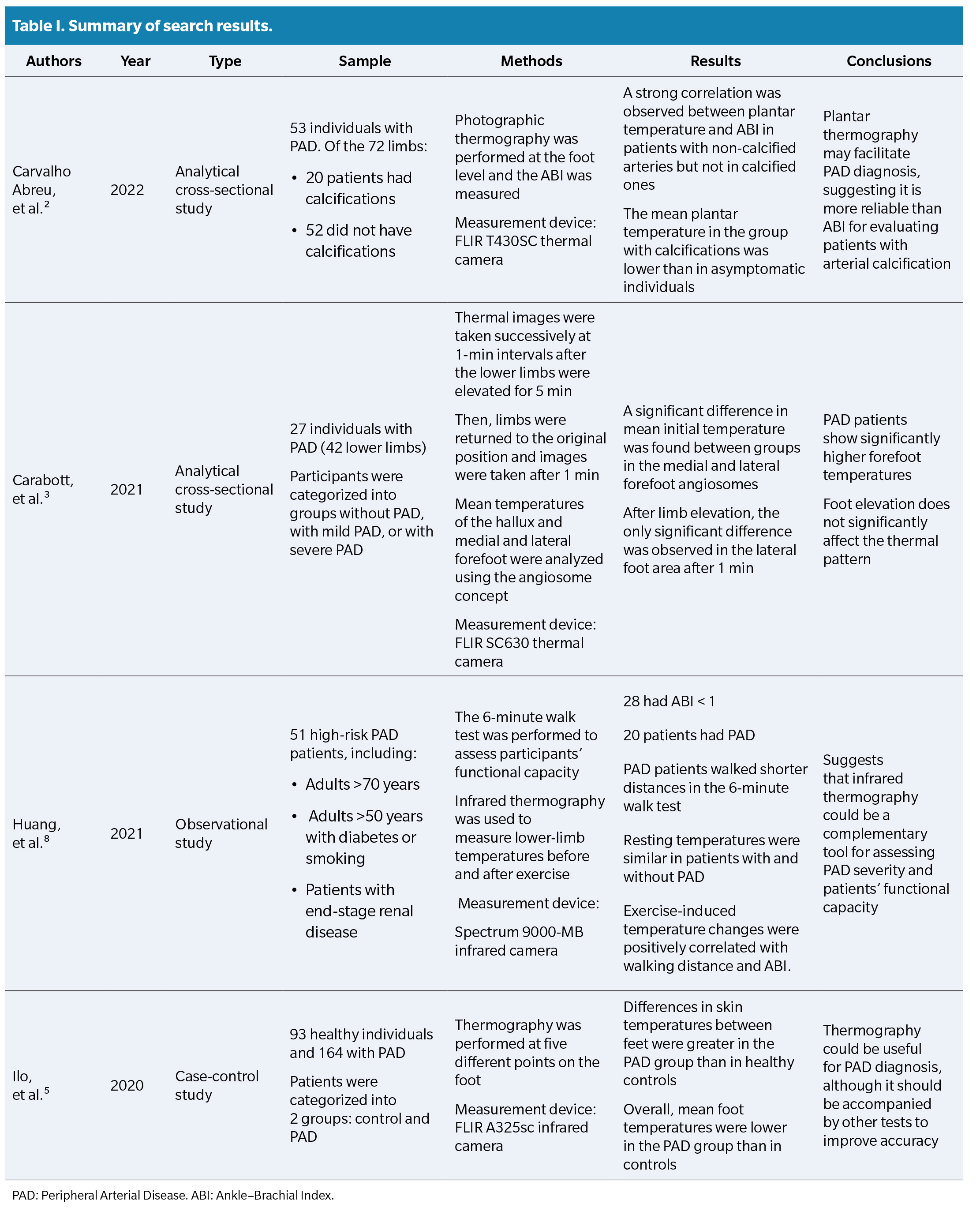

A total of four studies met inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1).

In the study by Carvalho Abreu et al. (2), the ABI was measured in 53 patients with PAD. Qualitatively, the study described that blue and purple colors in thermography were associated with lower ABI and more severe symptoms, while yellow and red corresponded to higher ABI and milder symptoms, supporting a positive correlation between ABI and temperature. The correlation between ABI and mean plantar temperature was significant in patients without arterial calcification (p < 0.05) but not in those with calcified arteries (p = 0.2174). Patients with calcified arteries showed higher ABI values than asymptomatic patients according to the Fontaine classification, despite having plantar temperatures similar to those with moderate PAD. This suggests that thermography may be more reliable than ABI in assessing patients with arterial calcification.

In the study by Carabott et al. (3), 42 limbs were analyzed, grouped as no PAD, mild PAD, or severe PAD. Successive thermograms were taken at 1-minute intervals during 5 minutes of leg elevation, followed by another recording after returning to baseline position. Resting mean temperatures of all angiosomes were higher in PAD patients than in controls. Significant differences in initial mean temperature were found in the medial (p = 0.048) and lateral (p = 0.049) forefoot angiosomes, though not in the hallux (p = 0.165). This “novel” finding, according to the authors, contrasts with the common expectation that an ischemic limb would be cooler. They proposed that the increased heat emission could result from altered thermoregulatory mechanisms, where local ischemia disrupts sympathetic noradrenergic vasoconstriction, increasing superficial cutaneous flow rather than deep arterial flow.

The study by Ilo et al. (5) included two groups: a control group (n = 93) and a PAD group (n = 164), the latter subdivided according to ABI (normal/mild/severe). Overall, mean foot temperatures were lower in PAD patients than in controls. Significant differences in inter-foot temperature (p < 0.001) were observed, being greater in PAD patients. The general trend showed lower mean temperatures in PAD feet, though not statistically significant in all measurements (e.g., distal plantar areas). Within the PAD group, foot temperatures were slightly higher in mild PAD compared to normal or severe cases, though not significantly so. The authors explained that in critical chronic ischemia, tissues maximize oxygen extraction, stimulating vasodilation—which could explain the slightly higher temperatures in mild PAD. In severe ischemia, these reserves are depleted, and skin temperature decreases. Significant temperature differences were observed between control and PAD groups in both the upper and lower foot regions. The study concluded that thermography can detect regional thermal differences but should not be used as a standalone diagnostic test; rather, it could serve as a complementary diagnostic tool.

In Huang et al. (8), 51 PAD patients were analyzed. Thermography was used to record skin temperature after a walking test. Resting leg and plantar temperatures were similar between PAD and non-PAD patients. However, post-exercise temperatures showed marked differences: in non-PAD patients, skin temperature rose slightly (32.6 °C ρ 32.9 °C; ρ < 0.001), whereas in PAD patients, plantar temperature decreased sharply (31.0 °C ρ 29.7 °C; p < 0.001). The exercise-induced temperature difference was −1.25 °C in PAD versus −0.15 °C in non-PAD (ρ < 0.001). Thus, after exercise, temperature dropped in limbs with arterial stenosis but rose slightly in patent arteries. Exercise-induced plantar temperature changes correlated positively with both walking distance in the 6-minute walk test (Spearman’s ρ = 0.31, p = 0.03) and ABI (ρ = 0.48, p < 0.001). ROC curve analysis identified −0.99 °C as the optimal cutoff for PAD screening. The authors concluded that while resting temperatures do not differ significantly, the thermal response to exercise (temperature drop) is a key indicator of PAD presence and severity, supporting thermography as a non-invasive alternative for

PAD evaluation.

Discussion

Currently, multiple diagnostic and monitoring methods exist for PAD, each with its own advantages and limitations. The most commonly used include pulse palpation, ABI, Doppler ultrasound, TPM measurement, and arteriography, the latter being the gold standard(9).

Clinical palpation is simple and quick, detecting pulse or temperature differences between limbs often interpreted as signs of PAD. However, it is limited by subjectivity, examiner experience, and external factors such as edema or anatomy. A colder limb does not necessarily imply reduced perfusion and may lead to misinterpretation(5,9,10).

The ABI is the most widely used parameter for PAD detection and grading due to its simplicity and low cost. However, it can yield falsely elevated results in patients with calcified arteries—especially in those with DM or advanced chronic kidney disease—reducing diagnostic reliability. Its accuracy also varies with population, cutoff values, and technique, and may miss localized stenoses such as those in the pedal arch(2,5,6,7,8,10,13).

Doppler ultrasound is a non-invasive imaging modality providing real-time anatomical and hemodynamic information but is operator-dependent and limited by body habitus or bowel gas. Arterial calcification can hinder full assessment, and the therapeutic relevance of isolated Doppler findings remains uncertain(1,4,6,9).

The TPM represents an alternative in cases where the ABI is unreliable, but it also has limitations. It cannot be performed in patients with digital amputations, and results must be interpreted with caution, as multiple confounding factors can affect the relationship between measured pressures and clinical outcomes(4,5,7,9)

.

Finally, arteriography continues to be considered the gold standard due to its ability to directly visualize vascular anatomy. However, its use is restricted to specific contexts, such as surgical planning, because of its invasive nature and the risks associated with contrast media, radiation, and vascular access. These complications include contrast-induced nephropathy, allergic reactions, and puncture-site complications(1,2,6,9).

Thermography is a non-invasive imaging modality that uses infrared cameras to measure body surface temperature. Since it does not emit ionizing radiation, it allows for safe and unrestricted applications, enabling visualization of the thermal behavior of biological systems(2,5,8,10,11). This represents a significant contrast in cost and accessibility compared with arteriography and near-infrared fluorescence angiography, which are much more expensive(2). Thermography can be performed in most healthcare settings and requires no additional time or cost beyond camera acquisition(5,12). Moreover, advances in this technology have led to the development of portable, easy-to-use, and affordable infrared thermal systems that demand minimal operator training—emerging as a promising technology for PAD detection(2,3,5,11). Because of these characteristics, thermography is positioned as a promising complementary method in uncertain cases where other tests such as ABI are unreliable, as it does not depend on vascular access or arterial calcification2,5. Its potential as a diagnostic and screening tool at the primary care level makes it a much more accessible and lower-cost option for broader application compared to the invasive gold standard(2,5,6).

Regarding the results of the analyzed studies, both points of consensus and notable discrepancies were identified. Three of the four studies(2,5,8) reported a trend toward lower temperatures in PAD patients vs healthy subjects and described correlations with ABI, reinforcing the plausibility of thermography as a marker of peripheral perfusion. However, Carabott et al. (3) reported an unexpected finding: higher temperatures in certain forefoot regions of PAD patients, attributed to vasomotor dysregulation in the context of diabetes. This contradiction highlights the complexity of thermal interpretation and the need to standardize measurement protocols and conditions.

Another relevant aspect is the variability in methodology. While Carvalho Abreu et al. (2) and Ilo et al. (5) analyzed resting temperatures, Huang et al.(8) introduced an exercise test, demonstrating that thermal response to exertion discriminates better between PAD and non-PAD patients than baseline temperatures. This dynamic approach could represent a promising research direction, as it captures functional alterations not always detectable at rest.

The heterogeneity of thermographic devices used is also a critical factor. Although most studies specify the manufacturer and model, they rarely provide information on thermal resolution, emissivity, or calibration procedures, hindering direct comparison of results. This lack of standardization may affect the sensitivity and specificity of the technique. Therefore, future studies should provide detailed descriptions of device specifications, follow reporting guidelines such as STARD and use evaluation frameworks like COSMIN14,15. Similarly, adopting international standards such as ISO 18434-1:2008 or ASTM E1933 would help ensure the reproducibility of findings(12,16).

Overall, the available evidence suggests that thermography may provide valuable complementary information in the assessment of PAD, showing particular usefulness in contexts where other tests fail—such as in diabetic patients with arterial calcification. However, the limited number of studies, methodological heterogeneity, and divergent results prevent it from being considered a definitive diagnostic technique at present.

For future research, it is a priority to design prospective studies with larger sample sizes and standardized protocols to confirm the reproducibility of findings. It would be particularly relevant to explore the role of thermography in monitoring patients before and after revascularization procedures, in primary care screening, and in high-risk populations such as those with diabetes or chronic kidney disease. Only through high-quality studies and direct comparisons with reference techniques can the role of thermography in clinical practice be clearly defined.

Conclusions

Infrared thermography emerges as a promising tool to support the diagnosis and monitoring of PAD. Its advantages include its non-invasive nature, absence of ionizing radiation, ease of use, low relative cost, and potential to complement conventional tests in clinical situations where these show limitations. However, the available evidence remains scarce and heterogeneous, with only four studies differing in methodology, devices, and findings. Therefore, thermography cannot yet be considered a definitive or standalone diagnostic method for PAD. Its clinical use should be regarded as complementary to other diagnostic techniques, potentially providing added value in specific contexts such as DM or arterial calcification, where ABI is less reliable. Future studies with more consistent designs and standardized devices and calibration are necessary to better define thermography’s role in clinical practice and establish its diagnostic validity.

Conflicts of interest

None declared

Funding

None declared

Contributions of the authors

Study conception and design: BIM, JML, JGC, DMC. Data collection: BIM, CSM. Analysis and interpretation: BIM, CSM. Drafting and writing: BIM, CSM, JGC, DMC. Final review: BIM, CSM, JML, JGC, DMC

References

- Medical Advisory Secretariat. Stenting for peripheral artery disease of the lower extremities: An evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2010;10(18):1-88.

- de Carvalho Abreu JA, de Oliveira RA, Martin AA. Correlation between ankle-brachial index and thermography measurements in patients with peripheral arterial disease. Vascular. 2022;30(1):88-96. DOI: 10.1177/1708538121996573.

- Carabott M, Formosa C, Mizzi A, Papanas N, Gatt A. Thermographic characteristics of the diabetic foot with peripheral arterial disease using the angiosome concept. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2021;129(2):93-8. DOI: 10.1055/a-0838-5209.

- Nativel M, Potier L, Alexandre L, Baillet-Blanco L, Ducasse E, Velho G, et al. Lower extremity arterial disease in patients with diabetes: A contemporary narrative review. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17(1):138. DOI: 10.1186/s12933-018-0781-1.

- Ilo A, Romsi P, Makela J. Infrared thermography as a diagnostic tool for peripheral artery disease. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2020;33(9):482-8. DOI: 10.1097/01.ASW.0000694156.62834.8b.

- Conte MS, Pomposelli FB, Clair DG, Geraghty PJ, McKinsey JF, et al. Society for Vascular Surgery practice guidelines for atherosclerotic occlusive disease of the lower extremities: management of asymptomatic disease and claudication. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61(3 Suppl):2S-41S.

- Aboyans V, Criqui MH, Abraham P, Allison MA, Creager MA, Diehm C, et al. Measurement and interpretation of the ankle-brachial index: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;126(24):2890-909. DOI: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318276fbcb.

- Huang CL, Wu YW, Hwang CL, Jong YS, Chao CL, Chen WJ, et al. The application of infrared thermography in evaluation of patients at high risk for lower extremity peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54(4):1074-80. DOI: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.03.287.

- Conte MS, Bradbury AW, Kolh P, White JV, Dick F, Fitridge R, et al. Global vascular guidelines on the management of chronic limb-threatening ischemia. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2019;58(1S):S1-S109 e33.

- Gatt A, Cassar K, Falzon O, Ellul C, Camilleri KP, Gauci J, et al. The identification of higher forefoot temperatures associated with peripheral arterial disease in type 2 diabetes mellitus as detected by thermography. Prim Care Diabetes. 2018;12(4):312-8. DOI: 10.1016/j.pcd.2018.01.001.

- Ring EF, Ammer K. Infrared thermal imaging in medicine. Physiol Meas. 2012;33(3):R33-46. DOI: 10.1088/0967-3334/33/3/R33.

- ISO. Condition monitoring and diagnostics of machines – Thermography – Part 1: General procedures. International Organization for Standardization. 2008.

- Lang PM, Schober GM, Rolke R, Wagner S, Hilge R, Offenbacher M, et al. Sensory neuropathy and signs of central sensitization in patients with peripheral arterial disease. Pain. 2006;124(1-2):190-200. DOI: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.04.011.

- Cohen JF, Korevaar DA, Altman DG, Bruns DE, Gatsonis CA, Hooft L, et al. STARD 2015 guidelines for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies: explanation and elaboration. BMJ Open. 2016;6(11):e012799. DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012799.

- Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL, et al. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(4):539-49. DOI: 10.1007/s11136-010-9606-8.

- International A. Standard Practice for Measuring and Compensating for Emissivity Using Infrared Imaging Radiometers (E1933-14). ASTM International. 2014.